Richard Wright (1908-1960) was a pioneering African American writer whose work powerfully captured the struggles and aspirations of Black people in America during the early 20th century. Born on September 4, 1908, on a plantation in Roxie, Mississippi, Wright’s early life was marked by poverty, instability, and racial violence, experiences that would profoundly influence his later literary career.

Wright’s childhood was tumultuous. His father abandoned the family when Richard was young, leaving his mother to struggle with raising her children. They moved frequently, living in various towns across Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee. Despite these hardships, Wright developed a love for reading and writing at an early age. His education was sporadic, but he completed the ninth grade, largely educating himself by voraciously reading anything he could find, including novels, magazines, and newspapers.

At the age of 17, Wright moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where he worked menial jobs to support himself. During this time, he began writing short stories and essays, which were often rejected by mainstream publications due to their unflinching portrayal of racism and the harsh realities faced by Black Americans. In 1927, Wright moved to Chicago, where he became involved in the Communist Party, seeing it as a vehicle for social change. His experiences with the party, however, were complex and ultimately disillusioning, but it provided him with a platform to express his political views and sharpen his writing.

We had our own civilization in Africa before we were captured and carried off to this land. We smelted iron, danced, made music and folk poems; we sculpted, worked in glass, spun cotton and wool, wove baskets and cloth. We invented a medium of exchange, mined silver and gold, made pottery and cutlery, we fashioned tools and utensils of brass, bronze, ivory, quartz, and granite. We had our own literature, our own systems of law, religion, medicine, science, and education.

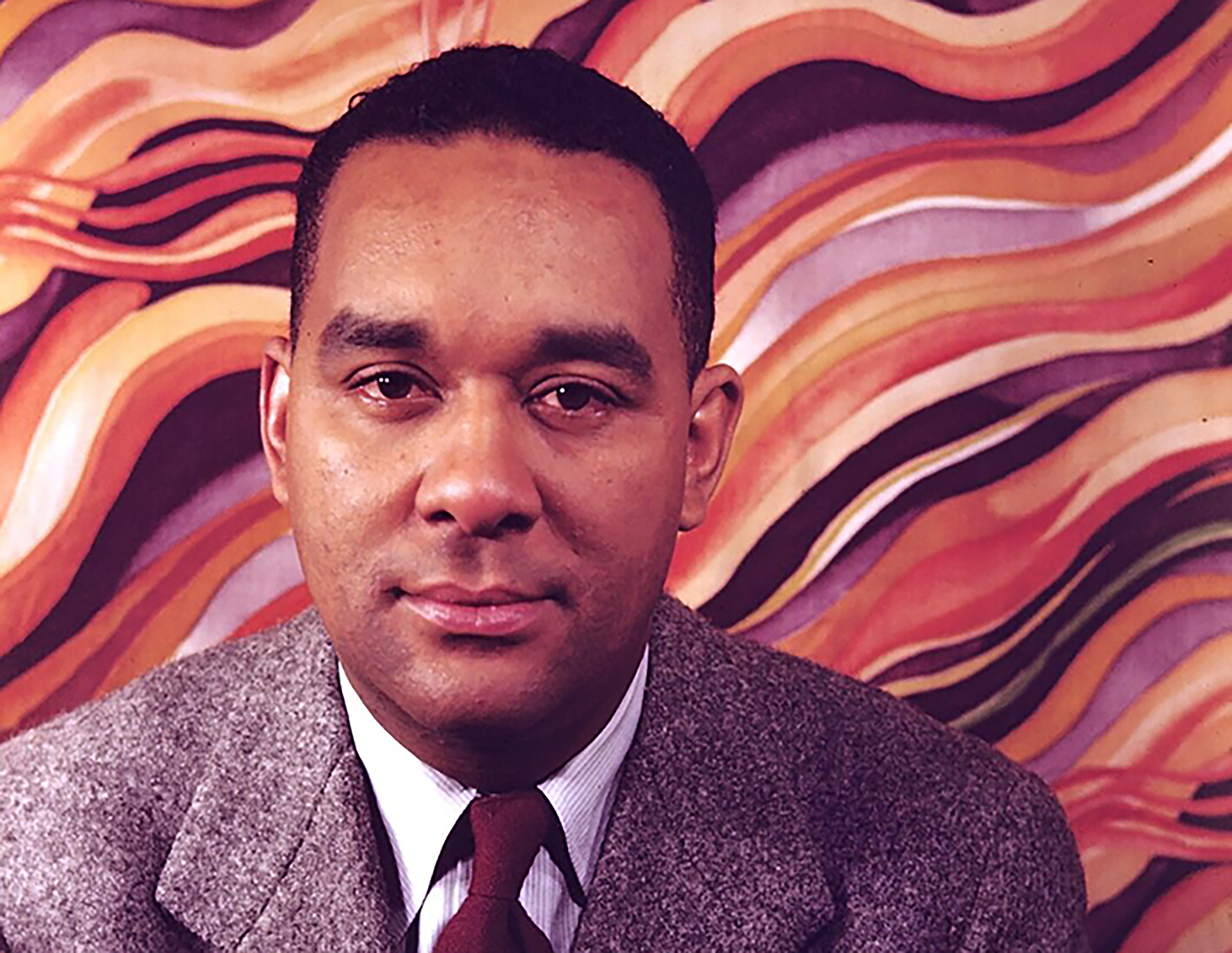

Richard Wright

Wright’s first major publication was a collection of short stories titled Uncle Tom’s Children (1938). The book was a critical success, earning him national recognition and a Guggenheim Fellowship. However, it was his novel Native Son (1940) that solidified his place in American literature. The story of Bigger Thomas, a young Black man living in Chicago who inadvertently kills a white woman, Native Son was a searing indictment of systemic racism and the brutal conditions that shaped the lives of African Americans. The novel became a bestseller and was later adapted into a stage play and film.

In 1945, Wright published his autobiography, Black Boy, which detailed his early life in the South and his journey toward becoming a writer. The book was another critical and commercial success, further establishing Wright as a leading voice in American literature. His work was characterized by its stark realism, unflinching portrayal of racial violence, and deep psychological insight into the effects of racism on both individuals and society.

Despite his success, Wright became increasingly disillusioned with the racial and political climate in the United States. In 1946, he moved to Paris, France, where he continued to write and engage with intellectuals, artists, and activists worldwide. His later works, including The Outsider (1953) and The Long Dream (1958), reflected his growing interest in existentialism and global liberation movements.

Men can starve from a lack of self-realization as much as they can from a lack of bread.

Richard Wright

Wright died of a heart attack in Paris on November 28, 1960, at the age of 52. His legacy as a pioneering Black writer endures, as his work resonates with readers and scholars worldwide. Richard Wright’s fearless exploration of race, identity, and power in America left an indelible mark on literature, making him a key figure in the canon of American letters.