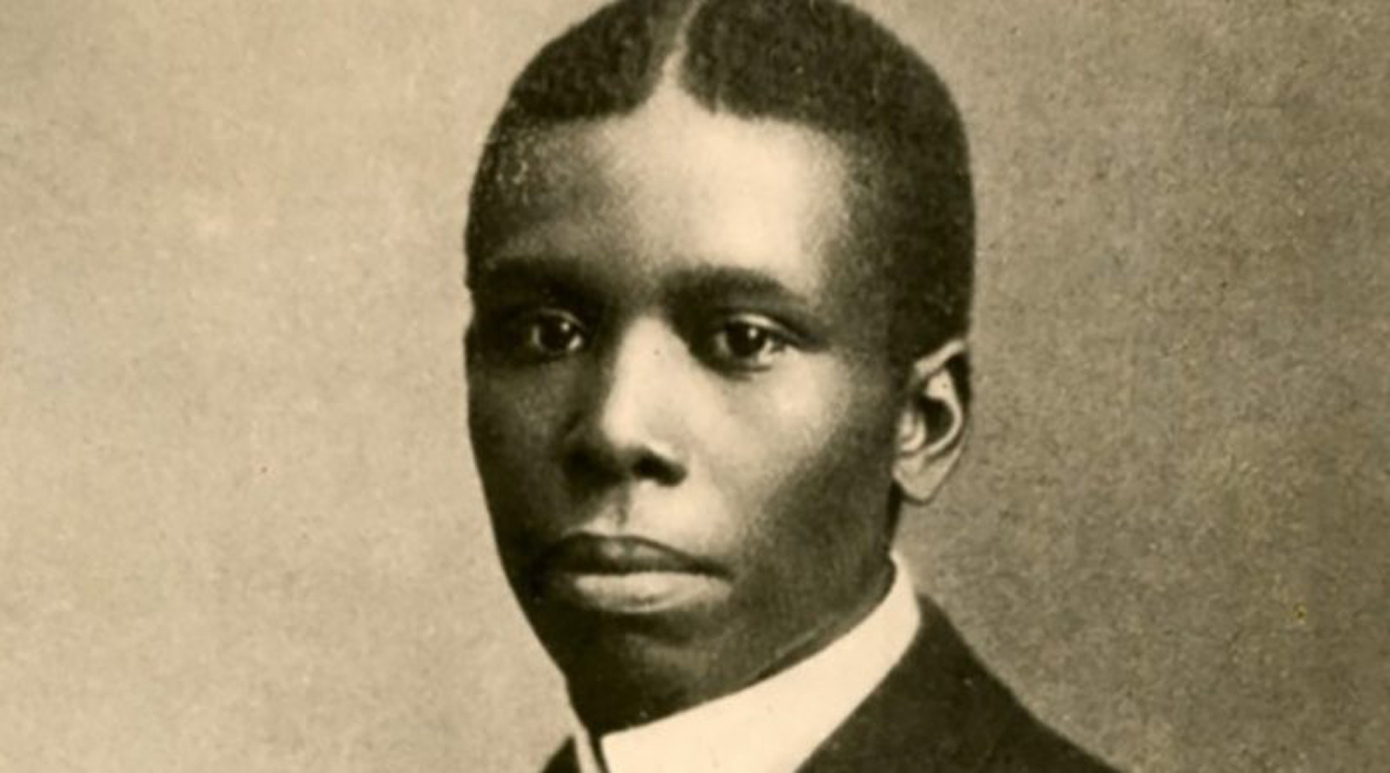

Paul Laurence Dunbar, a novelist, African-American poet, and playwright, significantly contributed to Black History and American literature. Living for a brief 33 years, Paul was a pioneer of sorts. He was the first black person to articulate the African American experience in diverse forms, from poems to newspaper articles, novels, operettas, ballads, short stories, and lyrics for Broadway musicals. His work laid the groundwork for the Harlem Renaissance, a period characterized by an explosion of cultural and literary talent. Paul was also the first black to write literature addressing both divides- the whites and the blacks.

Born in 1872 to Joshua and Matilda, Paul grew up in a low-income household, finding much support from his mother. His father died when he was 13 years old, leaving his mother to fend for Paul and his siblings. She was inclined to support Paul after discovering his gift in literal works at an early age. Dunbar wrote his first poem when he was only six years old and gave a public recital at nine. From then on, his mother assisted him in schoolwork and read him the Bible regularly, hoping that Paul would become a minister at the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Dunbar later joined Central High School, making him the first black person to study there. He was incredibly active as a student, earning a position as the class president, editor of the school newspaper, and the president of the school literary society. At the same time, he started Dayton’s first-ever African-American newspaper in African American history. He met Orville Wright, who became a friend and classmate while studying at the school.

After graduating, he secured a job as an elevator operator as his mother couldn’t raise funds to pay for his desired course. He would write while working, publishing his first volume of poems “Oak and Ivy” in 1893. Before publishing the poems, Paul was invited to talk to the Western Association of Writers at Dayton. During the meeting, Paul struck a friendship with James Newton Matthews, who brought his work to the spotlight. In a letter to the Illinois newspaper, Matthews praised Paul’s work. The letter was reprinted in newspapers nationwide, making Paul’s work recognized beyond Dayton. Thus, he didn’t struggle to market it when he released his first volume of poems. Paul received an offer to fund his college education shortly after, which he rejected. Given his newfound success in selling his first volume of poems, he wanted to pursue a literary career. Charles A. Thatcher, his would-be sponsor, agreed to help Dunbar find work in literary gatherings and libraries. He also met Henry A. Tobey who also helped him distribute copies of “Oak and Ivy” in Toledo. The two men teamed up to help Paul publish another verse collection “Majors and Minors” that included a dialect verse that found great readership among the white folk.

We wear the mask that grins and lies, it hides our cheeks and shades our eyes

Paul Laurence Dunbar

this debt we pay to human guile; with torn and bleeding hearts we smile.

Paul’s work also caught the attention of William Dean Howells, a realist writer who decided to review most of his literature. In a column dubbed Harper’s Weekly, William hailed Dunbar for describing his race objectively, commending the dialect poems as representations of Black speech. Dunbar also wrote lyrics for the first musical written and acted by African Americans “In Dahomey”. The musical was the first to appear on Broadway and was so successful that it toured the country and England for four years. He later began writing about white folks in his first novel, “The Uncalled”, which received much criticism. Paul followed it up with two novels, “The Fanatics” and “The Sport of the Gods”, which explored the lives and issues of the white culture. At the same time, Paul’s health began to deteriorate, suffering from tuberculosis, which didn’t have a cure at the time. And being an alcoholic only exacerbated the condition. He, however, did not falter in writing, releasing a collection of short stories “Lyrics of Love and Laughter” and “In Old Plantation Days”.

I know why the caged bird sings, ah me,

Paul Laurence Dunbar

When his wing is bruised and his bosom sore,

When he beats his bars and would be free;

It is not a carol of joy or glee,

But a prayer that he sends from his heart’s deep core,

But a plea, that upward to Heaven he flings

I know why the caged bird sings!

Paul lived with his mother in the last years of his life until February 1906. Even so, his work made an indelible mark in Black history online. His ability to use dialect to convey character and vast forms of literature laid the groundwork for many black writers.